On the human level, the image of Lajja Gauri acts as a temporal reference point, that is, the female giving birth, an auspicious occurrence: she is the embodiment of human fertility.

The representation of the goddess Lajja Gauri in Hindu iconography serves as a profound example of a symbolic image that undergoes continual generational, cultural, and artistic evolution, drawing on centuries of artistic and cultural layering of meaning. Despite being a common process in Indian art, the intricate development of such images has not received significant scholarly attention until now.

There has been no comprehensive cross-regional analysis, and the study of the forms, iconography, and iconology of Lajja Gauri images itself is a novel undertaking.

The broader inquiry revolves around understanding the iconographic formation of deity images in Indian art. This involves exploring the factors, contexts, and contingencies that contribute to the transformation of the form and meaning of a symbolic deity image. Until now, these issues have been largely overlooked in the field of Indian art history.

Much like Hindu mythology, the Lajja Gauri image conveys meaning on multiple levels simultaneously. On the human level, it serves as a temporal reference point, symbolizing the auspicious occurrence of female fertility and childbirth. On the divine level, Lajja Gauri embodies the concepts of fertility, generation, and life force. On the cosmic level, the image suggests universal laws and processes governing the generation of all life. Although mythic narratives about Lajja Gauri exist, some may be modern inventions, while others may preserve elements of the original meaning.

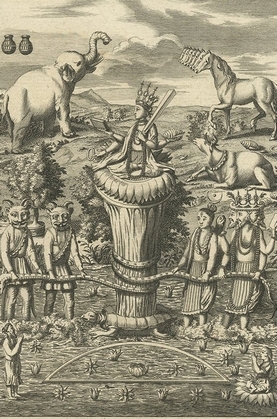

Artists creating images of Lajja Gauri drew upon ancient symbols of fortune, fertility, and life force, combining them within the female form in a birthlike position. These historical-religious symbols and images, continually reused and reincorporated, formed a new and enriched religious context, evolving into empowered cultural metaphors and visual morphemes in the language of Indian art.

An additional influential factor in artistic and iconographic formulation in Indian art is the frequent origination of deities in folk or village settings, later elevated to elite, pan-Indian, Brahmanical status. While this process is evident in reconstructed histories, such as that of the goddess Hariti, who transformed from a horrible yakshini to a revered deity, similar transformations can be assumed for many others, even if the steps are no longer clearly reconstructable from scattered images. Major deities often derived their theological and artistic foundations from combinations of elements initially found in minor village deities.

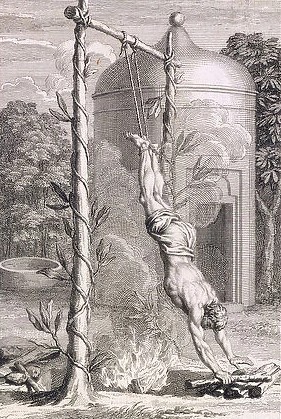

Lajja Gauri is consistently depicted reclining on her back in a supine position. The toes of the figure in repose are spread tensely, resembling the act of giving birth, despite the absence of any indication of pregnancy. Some scholars have suggested that the goddess is perceived as indecent or shameless due to this pose, interpreting it as a sign of sexual receptiveness. However, it's crucial to note that Indian goddesses, although capable of miraculous births, are never depicted as pregnant in either imagery or myth.

The ambiguity of Lajja Gauri's pose is likely intentional, as the positions of sexual receptivity and giving birth are deliberately similar. The human form and the birthing posture are utilized metaphorically to convey the concept of creation. In this image, human childbirth serves as a metaphor for divine creation.

The divine figures of the goddess Lajja Gauri, often adorned with halos, must be distinguished from mortal figures designed for erotic display. Failing to recognize this distinction overlooks the deeper meaning embedded in Lajja Gauri images. While they possess an erotic element, their primary purpose is not merely erotic but carries a profound spiritual message beneath the seemingly sensual display.

This mode of expression is familiar in Indian art, evident in the copulating maithuna figures adorning the walls of Khajuraho temples. These figures symbolize the ecstasy of union with the divine. Lajja Gauri has been labeled the "displayed female," yet despite the spread legs, only the vertical line of the pudendum is indicated. The intent is not vulgar or ribald, though the image does carry sexual suggestiveness. It differs significantly from images in which females expose their vulvas with their hands, representing mortal behavior in alignment with Tantric rituals. Such anonymous images express a different intent from those of the goddess Lajja Gauri, as she never uses her hands to reveal her sex organ.

Although artists carving Lajja Gauri images were likely aware of simpler erotic depictions, they set her image apart by incorporating rich symbolism. Despite this, the misconception that Lajja Gauri is solely erotic has hindered a thorough examination of her iconography and meaning. Misunderstandings about the image have become entrenched in literature, leading to its infrequent display in museums.

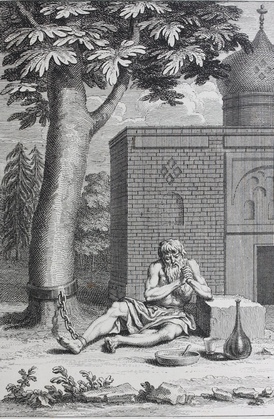

Devotion within Hinduism

Raising funds for hospital

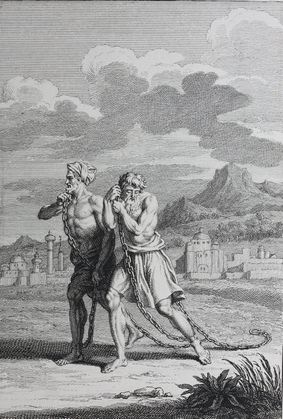

Depicting Brahmins

Depicting Brahmins

When one inversely examines nearly any of these instances, a notable observation arises: the pot-shaped belly area also remarkably resembles either a closed lotus bud or a phallus. The slit appears to function as the opening for both the vagina and the penis or lotus bud. This composite image, comprising the large bud and pot or phallus and womb, is unexpected but not uncommon in Indian art. Clever visual double entendre is prevalent, exemplified by images such as those in the Ajanta rock-cut vihara, depicting bodies of four deer sharing one head, or in the Badami rock-cut temple, portraying four wrestling gatas sharing two heads. Another instance is the frequently encountered elephant-bull, where two confronted bodies ingeniously share one head that can be perceived as either a bull's or an elephant's. Although these examples constitute a different class of optical illusion compared to Lajja Gauri images, as they are primarily physical conjunctions, the latter play on symbolic and sexual meanings.

When viewed from the "head" end, it appears that within the female body of Lajja Gauri, a phallus is enclosed in the womb area, or a lotus bud is within the kumbha, or pot. Indian literature, poetry, speech, and language itself thrive on punning, paradoxes, and multiple meanings. For instance, the word "kumbha" means both pot and womb.

In her analysis of cultural metaphors in the tenth-century Tamil text Tirumantiram, Margaret Egnor points out that a metaphor for the vagina in ancient texts is either an open flower or a ripe fruit. The womb is described as a lotus flower that rhythmically opens and closes in response to the presence and absence of the sun, and it is referred to as the "yoni" or the vessel that receives.

The penis is likened to a closed bud or a green fruit. All these associations find embodiment in Lajja Gauri images. Egnor further notes that the Tirumantiram straightforwardly describes conception as follows: "After the bud joins the flower, it blossoms." Lajja Gauri images seem to imply the union of the bud and the flower, the phallus and the womb. While the phallus is clearly depicted in images from Naganathakolla, Kudavelli, and Darasuram, it can be identified in almost all of the images.

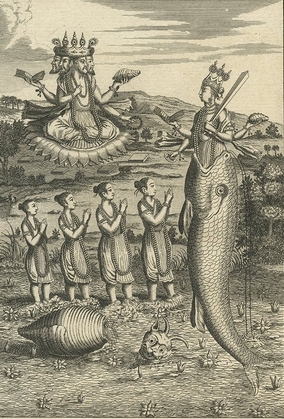

Matsya

Kurma

Varaha

Narasimha

The plaques, including those of Lajja Gauri from Darsi, Uppalapadu, and Kunidane, are dated to approximately the fourth century based on their resemblance to the Kondamotu figure, as noted by Sarma and Sivaramamurti. However, it's crucial to differentiate the depiction of Narasimha in the Lajja Gauri plaques from the Kondamotu plaque. While the sitting pose, style, and naivete of the man-lion figure are similar, the Kondamotu plaque is unequivocally Vaishnava. Unlike the lion in the Lajja Gauri plaques, the Kondamotu man-lion has four human arms holding Vishnu's implements, a Srivatsa on his chest, and an erect phallus.

The lion in the Darsi, Kunidane, and Uppalapadu plaques is distinctly animalistic, potentially representing the Sakti vahana, akin to lion faces carved on other plaques like Ter and Majati. These plaques appear to be cult images emphasizing the goddess's central position, indicating her equal status in size to Siva, Brahma, and either the man-lion form of Vishnu as Narasimha or the Sakti vahana. The goddess consistently forms a pair with the Sivalinga, suggesting that the male figure to her left could be Karttikeya, the son of Siva and Parvati. However, given the similarities in location and proportion to the kneeling Gujarati figure, it is equally plausible that he may be a Saivite devotee, attendant, or guard.

While the kneeling adoring figures in northern plaques had indiscernible genders, in the Ellora temple panel, standing attendants waving fly whisks were clearly female. Logic would suggest that the young male holding a lance or trident in the line-up of gods should be identified as Karttikeya. However, the identity of this male figure remains unresolved, as he sometimes holds a trident, which Karttikeya never does. Evidence from imagery carved on a temple in Orissa is persuasive in suggesting that he is a devotee or guard rather than Karttikeya. On the architrave of the doorway of the sixth to seventh century Satrugnesvara temple in Bhuvaneshvara, Orissa, Siva and Parvati, or Hara and Gauri, are depicted.