Camisards and Huguenots ethnicity and identity in the New World.

The formerly untold story of the Camisards and Huguenots is a quintessentially American story. Because the antecedents have been little worked on, it seemed vital not to tell this tale in isolation. It was necessary to establish the European context, the transcontinental connection, so that conflicts over Camisards and Huguenots ethnicity and identity in the New World could be more deeply understood as resulting from Old World precedents.

This rugged narrative serves as a symbolic rope tying together the experiences of the Old and New Worlds, posing perennial questions about identity, origin, survival, and the pursuit of success in a new land a narrative that resonates deeply with the American experience.

The French Protestant subculture, while not externally preserved, echoes through the corridors of "genealogical memory," exemplified by institutions like the Huguenot Society of America. This legacy, often termed Huguenot "mythmaking," involves passing down stories of ancestral courage in the face of adversity. The absence of an enduring external institutional framework in the New World may have contributed to the subculture's transformation. What persisted was a form of piety that, once driven underground or nestled within individual hearts, became elusive to scholars, its surface manifestations rare and challenging to trace.

Survival strategies of the Camisards, rooted in a pietistic reformulation of Reformed theology, paralleled the American experience of self-reinvention. As piety went subterranean, oral testimonies, crucial to understanding this history, faded away with their storytellers. Surviving sources include archives, confessional histories, supportive polemics, occasional biographies, and correspondences, yet a complete perspective or comprehensive documentation remains elusive.

The Camisards, a group of French Protestant rebels in the late 17th century, remain relatively obscure in historical narratives, overshadowed by more well-known events like the Huguenot struggles. However, their story is one of resilience, defiance, and religious fervor that deserves a closer examination.

The term "Camisard" is believed to have originated from the white linen shirts, or "camises," worn by these insurgents as a symbol of their resistance. The movement emerged in the Cevennes region of France, primarily among the Protestant population who refused to conform to the repressive measures imposed by Louis XIV after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. The revocation aimed to suppress Protestantism and consolidate Catholic dominance, leading to the persecution of Huguenots.

Themes of self-reinvention and self-help, integral to the American experience, find resonance in the Camisard and Huguenot survival strategies. In the absence of ministers, Camisards embraced lay prophets, foreshadowing a protodemocratic impulse that found fuller expression in the American colonies.

Figures like Gabriel Bernon, a master of self-reinvention, embodied the American spirit, navigating between religious fervor and financial gain, epitomizing the frontier tradition of blending profit with faith. His story, while quintessentially American, emerges from antecedents largely unknown to scholars, unveiling a complex tapestry of tribulation, triumph, and testimony.

The exploration of colonial religion gains depth with the inclusion of the less-explored Camisards, providing distinct insights into their subculture and its juxtaposition with Huguenots. This study delves into the direct clash between these two religious systems, unraveling their distinct styles of conversion, evangelization, and the ensuing political maneuvers as each group responded to the other. A significant episode, such as the 1700s slave uprising in New York, previously attributed to Elie Neau, now emerges with a focus on the theological principles that underpinned Neau's socially radical stance, alongside his personal experiences of enslavement and suffering.

The study draws from diverse sources, including Cotton Mather's publications of Neau's spiritual poetry and Carre's sermons, shedding light on Huguenot and Camisard modes of self-expression. These materials provide a basis for exploring various colonial connections, as exemplified by Amanda Porterfield's examination of female piety in the colonies. Notably, the Camisards' beginnings with women inspire prophets and the presence of female preachers among early Huguenots, like Marie Dentieres, offer fresh perspectives.

Furthermore, the study prompts a reevaluation of the Salem witch trials' impact on Cotton Mather's thoughts. It raises the question of whether the controversial and captivating nature of the trials has overshadowed Mather's concurrent focus on another crucial matter the status and significance of French Protestant refugees. By bringing attention to Mather's French connection, the study suggests a nuanced understanding of his simultaneous engagements with both the Salem witch trials and the cause of French Protestant refugees, inviting scholars to explore these interconnected threads.

The conflict erupted in July 1702 when the visionary Pierre Seguier, known as Esprit Seguier, proclaimed during an assembly that he had been called by the Spirit to free prisoners who had been apprehended and subjected to torture by the abbot of Chaila at Pont-de-Montvert. Accompanied by Abraham Mazel, Seguier and a group of 40 men undertook a night march, encircling the presbytery.

Breaking through the doors, they liberated the prisoners, dispatched the abbot, and set the building ablaze. Buoyed by their triumph, they proceeded to burn two churches and took the lives of eleven Catholics. Three assailants, including Seguier, were captured and subjected to torture, culminating in Seguier's execution by burning at the stake in Pont-de-Montvert.

Emboldened by their initial success, the Camisards, under the leadership of figures like Abraham Mazel, Gedeon Laporte, Jean Cavalier, and Salomon Couderc, unleashed a wave of chaos throughout the Cevennes. They adhered to the Old Testament principle of talion, retaliating by destroying churches in response to the burning of their temples. Their actions instilled fear among village priests, many of whom sought refuge in nearby cities.

In many important respects, the Camisards clung to their Reformed roots more tenaciously than Calvinists in Geneva, who might be said to have traded the conviction of the Reformation for the safety of structured ecclesiology. For instance, echoing some of the same arguments as those advanced a century earlier by Calvinist tyrannomach theorists such as Francois Hotman and Philippe Duplessis - Mornay, the Camisard prophets asserted that Louis XIV agents no longer did Gods will, because they persecuted the king's subjects, and that armed resistance to such an abuse of power was allowed by scripture.

In Holland, exiled Camisards, spurred on by Cavalier, devised strategies to reignite the rebellion. However, upon learning of this plan, Louis XIV dispatched envoys to Bern, Zurich, and the Low Countries to discourage support for a renewed Camisard uprising. The exiled rebels, facing dwindling options, were compelled to seek refuge in Wurtemberg. Berwick, in an effort to quell resistance, announced amnesty for any Camisard willing to surrender. While some chose to turn themselves in, others managed to elude capture by escaping into exile. Two resolute leaders who resisted capture met grisly fates, with Salomon Couderc being apprehended while clandestinely attempting to reenter France, aspiring to revive the Camisard rebellion. Unfortunately, only a handful of Camisards survived this tumultuous period.

With the advent of the Peace of Utrecht, France was once again hailed as the centerpiece in the Pope's Catholic realm. As the war ravaged region gradually regained a semblance of normalcy, efforts were made to reintroduce ecclesiastical structures in the Cevennes. Drawing inspiration from the Genevan synodal model, a cornerstone of Reformed church polity, the first synod of the Camisard Church of the Desert was established at Saint-Hippolyte-du-Fort in 1715. Identifying themselves as "Calvinistes," the Camisards, despite being unable to worship in temples, conducted Calvinist services during and after the persecutions. Deprived of clergy during this period, they developed an enthusiastic, ejaculatory prayer style, constantly seeking signs and wonders. This fervent piety influenced the worship style of the Pietist conventicle, bearing resemblances to the Puritan piety encountered later in the New World.

Camisard worship encompassed extensive psalm singing, utilizing the Huguenot Psalter published in 1551 in Geneva, where forty nine psalms were translated by Clement Marot, commissioned by Calvin. Tobie Rocayrol, a contemporary Calvinist, noted the striking similarity between a Camisard service and one in Geneva. In their zeal to proclaim God's word, the laity engaged in "plain style" biblical exegesis, coupled with practical exposition applicable to daily life, echoing Calvin's recommendations. Despite the adversities, Camisards staunchly observed the Sabbath.

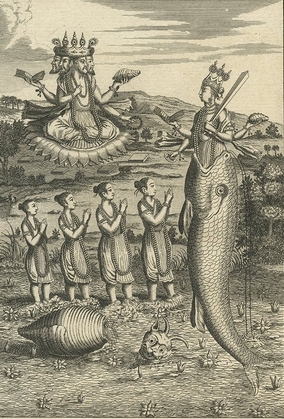

Matsya

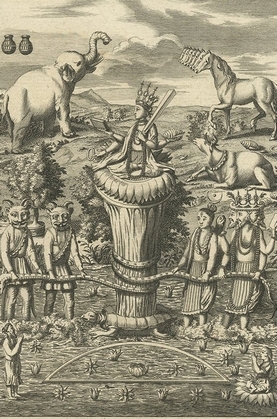

Kurma

Varaha

Narasimha

As the Reformed church gradually reestablished itself post-persecution, the Camisards embraced numerous Calvinist practices and beliefs. They partook in the Lord's Supper four times a year, mirroring the Geneva custom, and "fenced the table" against those considered morally unworthy or spiritually unprepared for communion. Embracing the doctrine of the "priesthood of all believers," they recognized only two sacraments and advocated for the cessation of clerical orders, declaring, "Long live God and the King! Death to the clergy!"

Even while evading pursuit by the king's soldiers, Camisard prophets instituted a vigilante form of moral surveillance reminiscent of Calvin's consistory. This involved punishing transgressions such as gambling, obscenity, and blasphemy. The Camisards also exhibited a keen concern for social welfare, mirroring Calvin's teachings by emphasizing stewardship and communal access to their limited resources, along with promoting Christian charity among fellow believers.

A letter penned on June 30, 1705, provides a glimpse into the piety of the Camisards. Authored by Commandant Boville of the dragoons, a devout Catholic, the letter recounts an encounter between the king's troops and several Camisards along the riverbank. The scene unfolds with one of them engrossed in reading the Bible, while others engage in washing in the stream. The troops, firing from a distance, managed to wound two, including the individual holding the Bible. Despite the injuries, the Camisards swiftly fled into the woods, eluding capture.

Jacques Bonbonnoux, the military leader turned pastor among the Camisards, narrated his experience of traversing snowy terrain at night to reach the designated mountaintop for worship. Singing psalms with a congregation exceeding a thousand believers, they braved the wind, with the preacher's spirited words resonating above the elements. Bonbonnoux recounted witnessing a man nearby immersed in ecstasy for four hours, kneeling and entreating a star to descend into one outstretched palm while praying for a dove to alight on the other.

The Camisard saga is imbued with legendary elements, yet a kernel of truth underlies the folklore. The Protestant community in France, resilient against assaults from Versailles and provincial delegates, withstood the challenges posed by the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Despite the perilous circumstances, the revocation failed to eradicate the Protestants or their steadfast beliefs. Louis XIV, aiming to eradicate Protestantism entirely from France and eliminate the Huguenot remnant tenaciously holding onto their creed in rural enclaves, encountered unforeseen internal and external political ramifications. The Revocation, intended as a decisive blow to eliminate this perceived religious anomaly, only succeeded in intensifying political complexities within and beyond the kingdom.

Preachers, prophets, and pastors among the surviving Camisards took to documenting their narratives, ensuring that their stories were preserved in written form. Even those who were not literate found a way to transmit their experiences, sharing them with transcribers. Recognizing the imperative to inspire fellow believers still facing challenges due to their faith, these Camisards offered their personal journeys as exemplars, illustrating the revelation of God's will amid adversity.

The narratives are both captivating and deeply embodied, chronicling the testimonies of individuals whose characters were forged in the crucible of trials, demonstrating a profound willingness to transcend self interest in pursuit of their understanding of God and freedom.