Camisards known as the galley preacher.

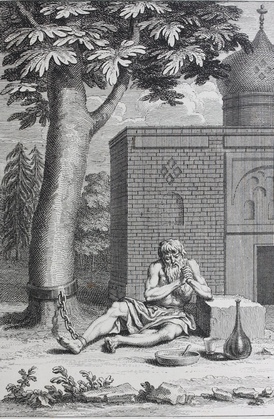

Elie Neau, a devout prisoner for his faith, endured the confines of a grave-like cell with minimal ventilation, preventing him from walking or standing. The tiny aperture allowed only a meager influx of air, while the cell itself was filled with filth. Despite the deplorable conditions, Neau did not succumb to despair. He found solace in his unwavering faith, believing that God would protect him until the end, echoing the words of the prophet Isaiah.

Born in Saintonge in 1662, Neau, despite humble beginnings, taught himself to read and write. Initially a sailor like many from Rochelle, he eventually became a prosperous merchant, conducting trade across the Atlantic and developing ties with the Camisards in the south of France. Fleeing the dragonnades, he sought refuge in the Americas and later settled in Boston after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. There, he married Suzanne Pare, a fellow French refugee, and they moved to New York in 1690.

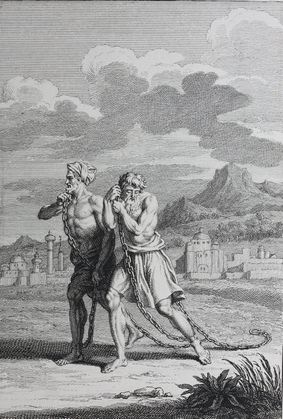

In 1692, while returning to London from New York, Neau was captured by a French navy privateer due to his identification as a French Protestant. This led to his sentencing to the galleys in France, where he faced the choice of renouncing his Reformed faith or enduring imprisonment. Resolute in his convictions, he refused to abjure and faced trial for his steadfast commitment to Jesus.

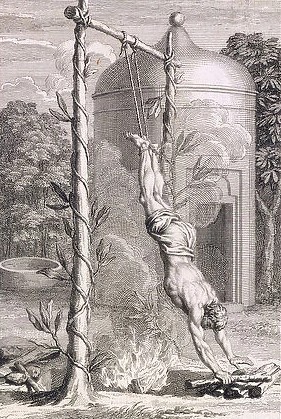

Sent to a galley in Marseille, Neau spent years chained alongside fellow slaves, using the opportunity to share the gospel through preaching, prayers, and song. He considered his chains a paradoxical form of freedom, as they liberated him from the shackles of sin. Despite solitary confinement for his unyielding faith, known as the "galley preacher," Neau continued to convert others through passive resistance, a strategy distinct from the later militant piety of the Camisard uprising.

Because of Neau's firm convictions, willingness to preach the Gospel, and courageous, exemplary behavior, he converted many men on board the galley. His long-suffering patience in the face of all trials marvelously inspired all those who witnessed it. His pious Christian speeches drew the attention of the entire galley; the example of a saintly, religious life, accompanied by the kindness that is the true nature of Christianity, caused even the most hardened of scoundrels to admire him; his hatred for evil; his constant concern to convert evildoers and to inspire a holy life in the heart of the corrupt; caused . . . many to give their lives to God and convert.

Amidst the harsh conditions of the galleys, Elie Neau's unwavering contempt for Rome incensed the Chaplain of the Galley. Chained with 200 other prisoners, mostly Camisards, Neau endured the grueling labor and inhuman treatment for six years. The repercussions of the Cevennes revolt intensified their suffering, subjecting them to particularly brutal punishments.

Despite being placed in irons and solitary confinement by a Catholic priest, Neau persisted in his passive resistance, fervently singing hymns and reciting psalms, earning him frequent beatings. Drawing inspiration from 1 Corinthians 1:27, he saw himself as an embodiment of God choosing the weak to shame the mighty. In May 1694, he was transferred from the galley to prevent further proselytizing and confined to a high tower, then a lightless cell on land. In an extraordinary turn of events, Neau acquired a Bible, which he concealed from his jailers.

By July 1696, he found himself imprisoned in the notorious Chateau d'Yf, miraculously eluding detection of the precious book that became a source of solace in his dark cell. Pastor Morin, a Reformed Walloon minister and Neau's steadfast correspondent, recounted this episode as a testament to divine intervention.

Enduring six months of solitary confinement in a cell tailored to his body's size and shape, devoid of light, and compelled to defecate beneath him, Elie Neau found resilience in fervent hymn-singing. He exhorted fellow prisoners through the walls, emphasizing the shared suffering of believers. Later, Neau was confined with three Camisard companions in a lightless cell meant for one person, fostering a communal expression of Camisard piety reminiscent of the early Christian church.

Facing deprivation, they practiced the Camisard tradition of sharing possessions for the common good. Neau occasionally smuggled letters out of prison, maintaining correspondence with Pastor Morin, who validated his faith. In a letter dated November 5, 1696, Neau described the sufferings endured, framing his imprisonment as a manifestation of God's grace.

He emphasized the transformative power of Christ's wounds and word, claiming to be nourished by them despite the guards' attempts to starve him into recantation. His language mirrored that of Christian mystics, portraying his awareness of personal insignificance and an immersion in divine grace.

Even in captivity, Neau viewed himself as part of the fight for the Reformed faith, dubbing his letter "From the Camp of the Lord." Later, in a shared cell, he regarded their Christian society as the "true Promised Land."

Beyond his spiritual resilience, Neau demonstrated practical acumen, procuring a stub of candle and sending secret letters to a church in Belgium. Finally, on July 3, 1698, Louis XIV pardoned him, securing his release through the intercession of William III, King of England. Nearly blinded by years in darkness, Neau, ever invoking God's light, was set free from his physical prison.

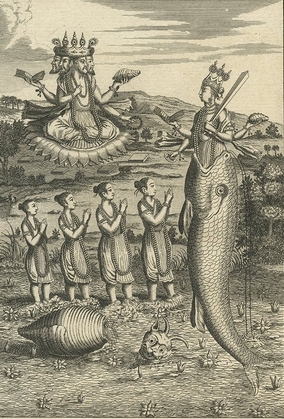

Devotion within Hinduism

Raising funds for hospital

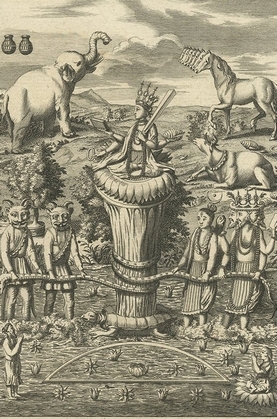

Depicting Brahmins

Depicting Brahmins

As if symbolically staking a Calvinist claim on the Continent with each step, Elie Neau ventured into several Swiss cantons, notably Bern, where he implored assistance for imprisoned comrades. Embarking on a preaching and proselytizing tour across Europe, he secured personal audiences with William III, seeking the release of fellow believers. A letter from Ragatz, dated September 10, 1696, expressed faith in Neau's ability to advocate for their cause, considering him illuminated by saving grace a recognition of Neau as one of the Camisards' own.

Effective in his plea, Neau facilitated the release of Camisard prisoners, earning admiration as a model and hero among French Protestants. His example was explicitly cited in a document drafted by Protestant galley slaves, regulating their conduct and pledging mutual support. Elie Neau, recently freed, had inspired them through his proselytizing efforts among fellow prisoners.

Continuing his advocacy, Neau left France for Holland in September 1697, bringing the plight of Camisards to the attention of William III. Journeying to London, he eventually sailed back to New York, reuniting with his family. Acclaimed by the French Church of New York as an unwavering confessor of the Reformed faith, Neau was praised for boldly declaring his allegiance to Jesus Christ.

In 1705, Elie Neau aligned himself with the Church of England in America, despite the Anglican liturgy, maintaining the Reformed piety rooted in his Calvinist heritage. Cotton Mather translated Neau's spiritual songs and cantiques from French to English, and published them together with one of Neau's letters from prison to his wife under the title A Present from a Farr Countrie. Mather regarded Neau as a model Christian. In his preface, Mather exhorted readers to model their piety after Neau's.

Matsya

Kurma

Varaha

Narasimha

The French Protestant refugees seeking religious freedom and protection from persecution in the New World significantly shaped colonial America, particularly in New York City. Among them, Elie Neau emerged as a key figure, contributing profoundly to governmental, social, and economic structures while influencing the burgeoning nation's ideology. His writings, resonating with the Camisard metaphor, marked a renewal of Protestant piety in America and Europe during the 1690s.

Neau played a pivotal role in the revival of Protestant piety in the Middle Colonies, especially New York. Despite later attending an Anglican church and having his daughter baptized there, he maintained connections with prominent social, political, and religious figures. Neau collaborated with Gabriel Bernon in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and had ties with Cotton Mather. As a catechist for the SPG, he began preaching to slaves, eventually establishing a school in a chapel within his home.

Recognizing the importance of support from the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), Neau embraced Anglicanism and worked toward church collaboration in New York, showcasing his early and ardent ecumenism. He continued participating in the Huguenot Wednesday Devotional Society while fostering a vision of a school for African slaves. The chapel in his home became the first school in America, emphasizing education for slaves, poor whites, and indigenous people.

Neau faced challenges, including threats from whites during a 1712 riot of black slaves in New York, as a result of his advocacy for education and humane treatment. Despite these challenges, he persevered in his mission until his death. In his will, Neau demonstrated unwavering support for the Camisards, allocating funds to perpetuate the moral precepts learned during his time as a galley slave. He bequeathed amounts for the poor, pastors, and the publication of his poems in French, leaving a lasting legacy of compassion and commitment.